Open star clusters are some of the most accessible deep sky objects, with numerous examples being visible to the naked eye, binoculars and telescopes.

A few have been known since ancient times, while many more were discovered in the 17th and 18th centuries, following the invention of the telescope.

There are 26 in the Messier catalog, another 469 in the New General Catalog (NGC) and approximately a further 600 that are known and have been catalogued – but this is just a drop compared to the 40,000 that are thought to exist within the Milky Way.

Some open star clusters have been known for thousands of years. Some can be visually breathtaking through the eyepiece, while others are stunning in photographs. But what exactly is an open star cluster? And which are the best ones to observe?

What is an Open Star Cluster?

Stars are born from nebulae, which are huge clouds of gas and dust in space.

As the molecules within the cloud drift through space, they collide with other molecules, forming denser patches. Over time, these patches grow in both size and mass, and as the mass of the patch increases, so does its gravity.

All the while, the patch continues to drift through the cloud, growing larger and more massive as it sweeps up more material.

As the patch grows more massive, the material that forms it is condensed at its core, causing the temperature of the material to rise in the process. Eventually, it becomes so massive that it collapses (essentially imploding) and ignites. Any remaining gas and dust orbiting the star can potentially form planets, moons, asteroids and comets.

It’s not unusual for several patches to form close to one another; if the patches are close enough, they could form a multiple star system.

Alternatively, numerous stars can form within the same region, giving rise to an open star cluster. Whether the end result is a single star, a multiple star or a open star cluster, the whole process takes several million years to complete – nothing more than the blink of an eye in the lifetime of the universe!

Since we’re looking at these stars at the beginning of their lives, the stars in open star clusters are young, hot and frequently appear blue-white.

Occasionally, you’ll find some clusters with a few older stars that appear coppery or orange in color, but many open star clusters will lack a great variety of color. However, they’re far from dull, and often have the appearance of tiny diamonds on black satin.

Open star clusters typically contain hundreds or even thousands of stars, and although they appear close together, they won’t always remain this way.

Over time, the individual stars will drift apart, and while some will remain relatively close to one another and even share the same path through space (a stellar association) many will simply go their own way.

A Brief History of Open Star Clusters

Ancient Skies

There are a number of open star clusters that are visible to the naked eye and, therefore, have been known for thousands of years. The best known of the these, the Pleiades, is so conspicuous that civilizations around the world have revered it and associated legends with it.

For example, the ancient Greeks saw them as being the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas, hence their alternate name, the Seven Sisters. Many other cultures typically saw them as seven young girls or wives, while the Native American Blackfoot tribes saw them as orphaned boys.

The Pleiades can be found in the constellation Taurus, the Bull, which is also home to the Hyades star cluster, a large group that forms a V-shape representing the head of the bull. Both these clusters are bright enough and large enough to be visible with the naked eye from suburban skies.

Toward the east is Cancer, the Crab, home to the Praesepe (or Beehive) open star cluster. This cluster is unique, as it’s the only one whose stellar magnitude is brighter than any of the stars that form the constellation in which it resides.

Like the Pleiades, it has been known for thousands of years, but it also has the distinction that it was once used to predict the weather. If the cluster was clearly visible, then good weather could be expected. However, if the cluster was lost from view, then observers knew that rain was on its way.

Other clusters known since ancient times include the Coma Star Cluster, the Double Cluster (NGC 869/884), M7 and possibly M6.

The Greek astronomer Hipparchus first recorded the Praesepe and Double Cluster in the 2nd century BCE, while his compatriot, Ptolemy, first recorded M7 and (possibly) M6 some four hundred years later. Ptolemy is also credited with being the first to record the Coma Star Cluster at around the same time.

The 17th to 19th Centuries – The Age of Exploration

It’s possible that other clusters may have been seen over the years, but it wasn’t until the invention and widespread use of the telescope in the 17th century that things began to rapidly change.

Astronomers could now see fainter objects that were previously invisible to the naked eye, opening the door to the wider universe that lay beyond.

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Hodierna discovered another 13 clusters (14, if you count M6) by 1654, with another 25 open star clusters being found within the next 100 years.

In fact, it was their stellar nature, brightness and size that that made them so easy to find; globular clusters were small and misty, nebulae were faint, and while galaxies were also faint, they had the additional disadvantage of being relatively small.

By the time the French astronomer Charles Messier started compiling his famous catalog in the mid 18th century, there were around 45 open star clusters known to exist. Messier’s passion was comets, and his catalog was meant to help him identify any object that might be mistaken for a new cometary discovery.

The first edition, published in 1774, contained 45 objects, of which 17 were open star clusters, with six of these being discovered by Messier himself. Given that many more were known at the time, this raises an interesting question: Why did he include the Pleiades – which is clearly stellar, even to the naked eye, and could not be mistaken for a comet – but ignore the others?

There’s a theory that Messier only included the Pleiades as the last object in his list so that he could go ahead and publish it, but unfortunately, the truth is we’ll never know!

The next 100 years continued to see clusters being discovered at a rapid pace. Not only was this due to the telescope, but also the exploration of the southern hemisphere, whose stars and deep sky objects had largely remained undiscovered until that time.

Into the 21st Century

While the pace of discoveries may have since slowed, that doesn’t mean that nothing has changed. For example, there have been some deep sky objects that were previously thought to be open star clusters but are now considered to be merely chance alignments.

Messier himself fell afoul of this. Most astronomers today have adopted a final Messier catalog of 110 objects, but several of the open star clusters have been reclassified since Messier first included them.

For example, M24 in Sagittarius was often listed as a star cluster, but is now known to be a large concentration of stars within the Milky Way. Most famously, M73 was discovered by Messier in October 1780, and he originally described it as being a cluster of four stars, with some nebulosity.

However, it was conclusively proven to be a chance alignment in 2002, when studies showed that the stars lay at differing distances and were moving in different directions.

Another non-Messier example is Collinder 399, aka Al Sufi’s Cluster, Brocchi’s Cluster or, most famously, the Coathanger. This group of stars can be glimpsed with the naked eye under dark skies and has been known since antiquity, with the Persian astronomer Al Sufi recording it in the 10th century AD.

It’s always been a favorite with amateur astronomers as it resembles a coathanger through binoculars (hence its nickname), but its status as a true star cluster came into question in 1970.

More recent studies have shown that the stars are truly unrelated, but fortunately this doesn’t detract from the surprise of seeing a coathanger among the stars!

Lastly, in the past, it was always thought that there were two types of star cluster – open and globular – but astronomers have since added another two categories: stellar associations and super star clusters.

A stellar association is a group of stars that move together through space, but are not gravitationally bound together. As such, it’s thought that these stars are former members of the same open star cluster that have since drifted apart. One example of this are the seven bright stars that form the Big Dipper.

A super star cluster is a massive, young open star cluster, that’s believed will eventually evolve into a globular star cluster. As of today (late February 2023), less than ten are currently known, with five of those within either the Milky Way or its satellite galaxies, the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds.

How to Observe Open Star Clusters

As with everything else, there are three ways to observe open star clusters: with just your naked eye, with binoculars or with a telescope. As you might expect, what you’ll see will greatly depend upon the equipment – if any – you’re using.

A number of open star clusters are large enough to be enjoyed with binoculars – besides the aforementioned Pleiades and Beehive clusters, other examples include M41, M35, the Coma Star Cluster and the Hyades.

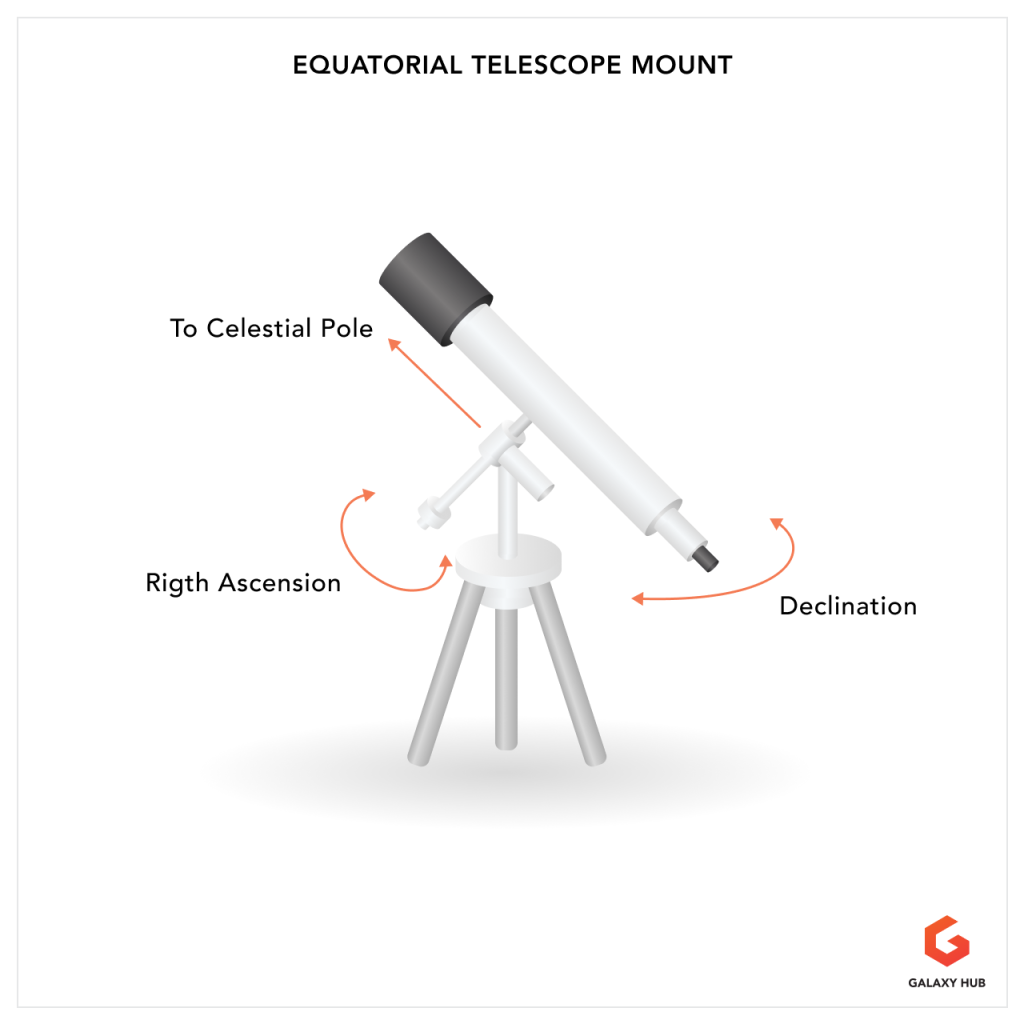

If you’re using a telescope, be sure to start with a low magnification, ideally with a wide field of view. Again, their large size means that the cluster might not completely fit within the field of view of a higher magnification eyepiece.

Regardless of how you observe open star clusters, the following key steps will help to ensure you get the best possible views:

- Find a dark location. Light pollution poses a terrible risk to amateur astronomy, as it brightens the sky and makes all but the brightest objects invisible. Consequently, you’ll ideally want to be far from any bright lights that might otherwise make observing open star clusters impossible.

- Allow your eyes to adapt to the dark. Most people’s eyes typically take about 90 minutes to properly adapt to the dark. This might seem like a long time, but once your eyes are dark adapted you’ll be able to spot star clusters that had previously eluded you, and see a much greater number of stars within them.

If you’re using a telescope, there’s one other important step: give your telescope time to cool down. You probably keep your telescope indoors, in which case the ambient air temperature outside may be colder than it is indoors. (This will obviously depend upon the time of year and, to a lesser extent, your latitude.)

When the temperature indoors is warmer than outside, warm air becomes trapped in the telescope tube and will need time to cool down. Otherwise, you could find the view shimmering, as you’ll be looking at your target through the turbulent warm air trapped inside your scope.

A small scope takes around 30 to 45 minutes to cool down, while the largest apertures could take hours, and it’s a good idea to factor in this time when planning your observing session.

Beyond these steps, perhaps the best thing you can do is use averted vision. This is the practice of looking at your target using your peripheral vision, or “out of the corner of your eye.”

Your eyes are made up of photoreceptors called cones and rods. The cones are located in the center of the retina and work best in daylight, when they help us to see color. The rods, however, are located at the edge of the retina and are more sensitive to light and movement, but not to color. For this reason, they are best suited to low-light and night-time conditions, where the lack of light mutes any available color.

When you look at your target with averted vision, you’re making use of the more sensitive rods, which can allow you to see fainter objects and stars in your peripheral vision. It’s remarkably effective at revealing previous unseen targets, and a well-established trick that’s been used by amateur astronomers for many years!

The Best Open Star Clusters to observe

M7

- M7 – If you have dark skies, you may be able to spot M7, Ptolemy’s Cluster, with the naked eye. It can be found very close to the two stars that mark the stinger of Scorpius, the Scorpion, and within the same binocular field of view as M6. Through the low-powered eyepiece of a telescope, the stars appear to form a flattened H shape, with a coppery star – the cluster’s brightest – located on the southwestern edge.

M44

- M44 – Naked eye observers under a dark sky may notice M44, the Praesepe or Beehive Cluster, roughly midway between Castor in Gemini and Regulus in Leo. Otherwise, binoculars provide a fine view, with many of the cluster’s individual stars being easily seen, even at low power. Although not as large as the Pleiades, this is another cluster you’ll need a low-powered eyepiece in order to fit it within the field of view, and, consequently, is best observed with binoculars.

M45

- M45 – Many amateur astronomers consider M45, the Pleiades, as being the best of its kind. It’s easily seen as a small group of stars with the naked eye, even from suburban skies, and is an outstanding sight through almost any binoculars. Telescopically, you’ll need a very low power eyepiece to fit the entire cluster within the field of view, making this another deep sky object best observed with binoculars. The Pleiades is also one of the most photographed objects in the sky, with stunning images showing the stars surrounded by a misty blue nebula.

NGC 869/884

- NGC 869/884 – It’s not hard to see how the Double Cluster got its name. This pair of open star clusters lie just just a little under half a degree apart and can both be glimpsed with the naked eye under dark skies or, better yet, with binoculars. They’re both roughly the same size and brightness, but of the two, you’ll see that NGC 869 is more compact, while NGC 884 has a number of deep orange stars on its southeastern edge.

NGC 4755

- NGC 4755 – Located in the southern hemisphere, just a degree from Beta Crucis, this is one cluster that frequently tops the wish-list of northern hemisphere observers. The 19th century astronomer John Herschel compared the cluster to a casket of precious stars, giving rise to its nickname, the Jewel Box Cluster. At magnitude 4, it can be glimpsed with the naked eye, while binoculars will show numerous stars of blue, yellow and orange.