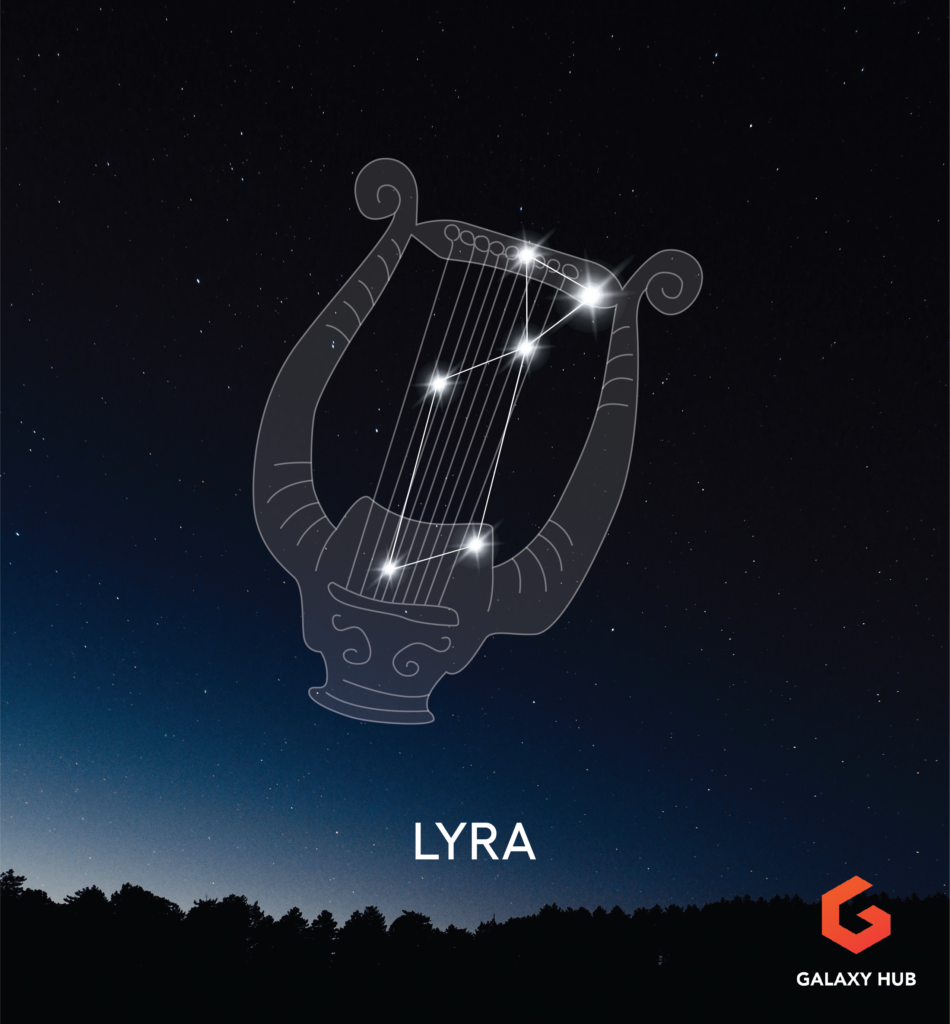

Lyra, the Lyre, is a compact constellation best seen from the northern hemisphere during the summer months, and it contains a number of features of interest to the amateur astronomer.

Firstly, there’s brilliant Vega, the constellation’s brightest star and the fifth brightest star in the sky overall. Vega makes the constellation easy to find, as it passes nearly overhead for many observers north of the equator.

Lyra is also home to Epsilon Lyrae, the famous “double double” star, and the equally famous Ring Nebula. Both sights are fine targets for telescopic observers and favorites with astronomers worldwide. If you’re looking for more, you can also try your hand at M56, a globular cluster, and the overlooked open cluster NGC 6791.

Lyra – Key Data

Name

| Latin | English | Pronunciation | Genitive | Abbreviation |

| Lyra | The Lyre | LYE-ruh | Lyrae | Lyr |

Location

| Hemisphere | Best Seen | R.A. | Declination |

| Northern | Early July to Late August | 18h 50m 48s | +36° 01’ 32” |

Features

| Area | Size Rank | # of Messier Objects | # of Stars Brighter than Mag 4 | Brightest Star |

| 286 sq. Deg. | 52nd | 2 | 3 | Alpha (Vega) Mag 0.0 |

Top Lyra Facts

- The constellation is best seen from early July to late August

- It ranks 52nd in size out of the 88 constellations

- It is one of the original 48 constellations first introduced by Ptolemy

- It represents the lyre of Orpheus in Greek mythology

- Vega, its brightest star, is the fifth brightest star in the sky

- Vega was once the Pole Star and will be again in about 12,000 years

- It is home to two Messier deep sky objects: M56 and M57

- Lyra is also home to Epsilon Lyrae, the famous “double double” star

Lyra in Mythology

According to Greek myth, Lyra represents the lyre invented by Hermes, who took an empty tortoise shell he found on the beach and strung seven strings across it. He later traded it with his half-brother, Apollo, who gave him a magical staff in return.

Apollo then passed it on to his son, Orpheus, whose music was said to be so beautiful that it could even charm stones and wild beasts. Orpheus joined Jason and his Argonauts on their quest for the Golden Fleece, and his talents proved useful when he was able to calm the Sirens who would otherwise lure the sailors to their deaths.

In time, Orpheus married Eurydice, but his beloved was later killed after stepping on a snake and dying from its bite. Orpheus traveled to the Underworld, where he used his lyre to charm the god Hades, thereby persuading him to allow Eurydice to return to the land of the living.

However, Hades agreed on one condition – as they departed, Eurydice must follow behind him and he must not look back until they were both outside.

Orpheus agreed, but he found it impossible to leave without looking behind to be sure his wife was following in his footsteps. The moment he did, Hades reclaimed Eurydice and Orpheus was forced to leave the Underworld without her.

Heartbroken and distraught, it’s said that Orpheus spent the remainder of his days roaming the land, playing the lyre and singing his songs, but always spurning the advances of the women charmed by his music.

Lyra in History

Lyra is one of the original 48 constellations listed in the 2nd century by the Greek astronomer Ptolemy, in his great work, the Almagest. As such, it has been in existence for thousands of years and has changed little in the intervening time.

Besides Ptolemy, other early astronomers often listed the constellation as a bird. For example, in India it was known as an eagle, and one early name was Aquilaris (similar to the constellation Aquila, the Eagle.) Uniquely, the Persian astronomer Al Sufi listed it as a goose.

However, most Arabic people knew it as a lyre, while those in Europe saw a similarly shaped harp, with early Britons associating it with the harp of King Arthur.

To some extent, its association with both an eagle and the lyre would later come together, as the lyre would often be depicted as being carried in the talons of an eagle in star charts.

When & How to See Lyra

Given its position in the sky, Lyra is a constellation that’s best seen from the northern hemisphere. The constellation passes almost directly overhead for observers in the mid-northern latitudes at around midnight (11pm standard time) in late July.

The opposite is true for most observers in the southern hemisphere. Observers further south than the tropics will find that it skims over the northern horizon during the winter months, but its lack of altitude will make observing deep sky objects problematic.

Thanks to Vega, its brightest star, the constellation is easily found. Vega is an unmistakable, brilliant white point of light and the brightest star in that area of the sky. If the Big Dipper is visible, draw a line north through Phecda and Megrez and keep going!

While you’re in the area, look for Deneb and Altair nearby, as these three stars make up the Summer Triangle.

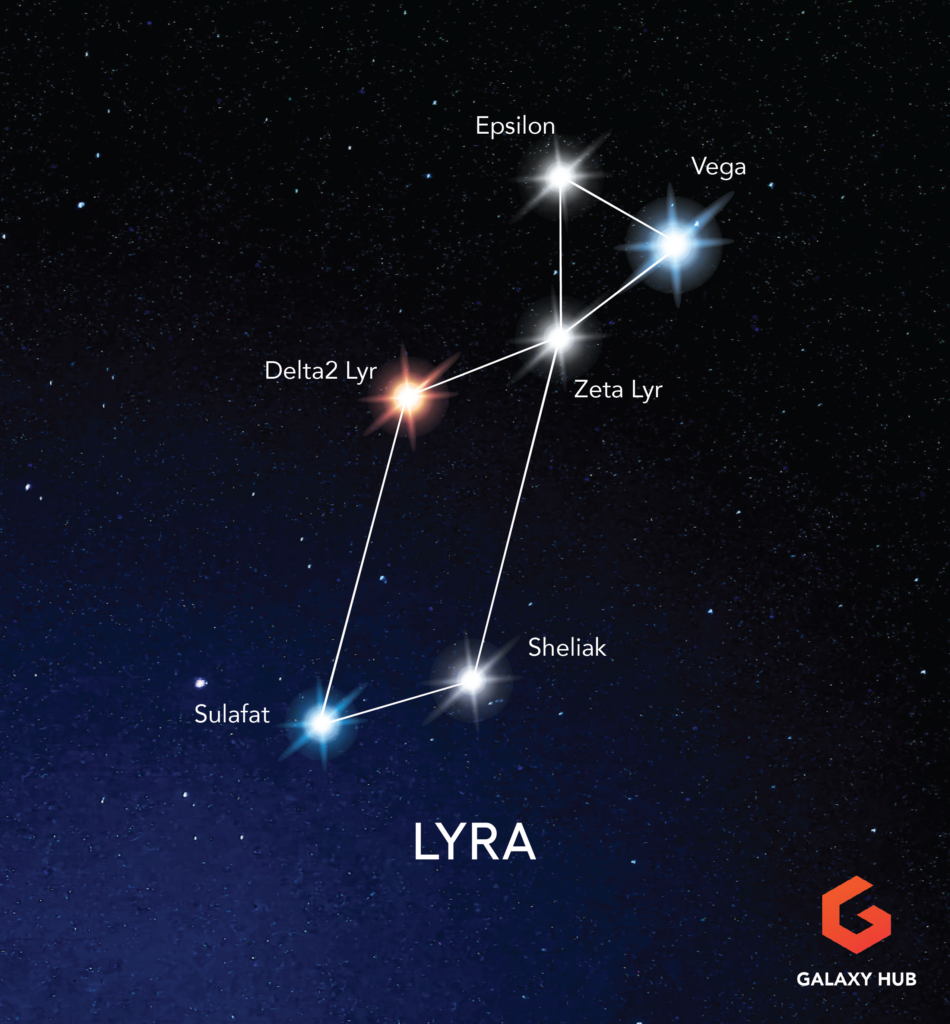

Lyra’s Notable Stars

| Bayer/Flamsteed Designation | Name (s) | Mag | R.A. | Dec. | Distance (LY) | Notes |

| Alpha / 3 | Vega | 0.0 | 18h 36m 56s | +38° 47’ 01” | 25 | Lyra’s brightest star |

| Gamma / 14 | Sulafat | 3.3 | 18h 58m 57s | +32° 41’ 22” | 634 | 2nd brightest star |

| Beta / 10 | Sheliak | 3.5 | 18h 50m 08s | +33° 21’ 46” | 881 | Eclipsing variable and a double for small telescopes |

| Epsilon / 4 | The Double Double | 5.0 | 18h 45m 08s | +39° 38’ 07” | 156 | Famous double star for binoculars and telescopes |

Alpha Lyrae (Vega)

The fifth brightest star in the entire night sky, Vega has been known to cultures across the world for thousands of years. Its name (originally, Wega), like those of so many other stars, is Arabic in origin, and is derived from waqi, which refers to an eagle or vulture, with which the constellation was originally associated.

However, it’s in Asian cultures that we find the most interesting legend associated with the star. The story originated in China but has since spread across the area and varies from country to country.

Vega typically represents a young maiden of noble birth (eg, a princess) whereas neighboring Altair (the brightest star in the constellation Aquila) is a young man of lower social standing (eg, a shepherd.) The two meet and fall in love, but their affair is forbidden by her father and the two are forever separated by a river, as represented by the Milky Way.

It’s only on the 7th day of the seventh month that the two can be together, when magpies form a bridge across the river with their wings for the pair to cross. If it rains that day, it’s said the magpies are unable to form their bridge across the rising water and the rain drops are the tears of the lovers, who must now wait another year to meet.

This myth is still celebrated today, notably in Japan, where it is remembered during the annual Tanabata, or Star Festival.

At just 25 light-years away, Vega itself is a nearby neighbor of the Sun, which helps to explain its brilliance. It’s a main sequence white star of spectral type A0, with an estimated age of 450 million years, or only about a tenth of the Sun’s, but with double its mass and 57 times its luminosity.

Beyond these facts, Vega has a number of other fascinating attributes. Firstly, it’s surrounded by a disc of dust, which is believed to be the debris remaining from collisions between various objects orbiting the star.

Vega could also be home to a number of planets, although none have been confirmed so far. Most recently, two planets, with masses similar to Neptune and Saturn, have been potentially identified, with further evidence required to prove their existence.

Lastly, Vega is a once-and-future pole star. Due to the gravitational influence of the Sun and Moon, the Earth’s axis “wobbles” over the course of 25,772 years.

During that time, the north polar star will appear to change, as the Earth’s axis points toward a different star in space. Right now, the north polar star is Polaris, in the constellation Ursa Minor, but 14,000 years ago it was Vega. It’ll next be the pole star again around 14,000 A.D.!

Gamma Lyrae (Sulafat)

Vega is, by far, the brightest star in Lyra, with Sulafat coming in a distant second. Its name is derived from the Arabic word for “turtle”, as lyres and harps were once made of tortoise shell. Sulafat has a luminosity roughly 2,400 times that of the Sun, but its distance – over 600 light-years – makes it appear much fainter.

It’s a blue-white giant star, nearly six times more massive than the Sun, that was once thought to be a close spectroscopic binary. However, recent studies have indicated that the star is most likely to be solitary.

Beta Lyrae (Sheliak)

Sheliak takes its name from Al Shilyāk, one of the Arabic names for the entire constellation, and can be seen as a double through any telescope at low power.

The primary (brightest) star – Sheliak – appears brilliant white and about four or five times brighter than its blue-white companion. However, this is an optical double, as the two stars are unrelated, with the fainter star being about three hundred light-years closer to us.

In reality, Sheliak itself is a spectroscopic binary, with the two stars being so close that one star is slowly cannibalizing the other. As such, they’re too close to be split optically, with the pair taking 12.9 days to orbit one another. However, as matter is transferred from one star to the other, this period is actually increasing at a rate of 19 seconds every year!

Fortunately, the orbit of the two stars is aligned with our view from Earth, making Sheliak an eclipsing binary. First discovered by the British astronomer John Goodricke in 1784, as one star passes in front of the other, the total light from Sheliak drops and the star appears to dim from Earth. Therefore, every 12.9 days, you’ll see its magnitude drop from its usual 3.25 to 4.36.

Epsilon Lyrae (The Double Double)

Without a doubt, Epsilon Lyrae, the famous “double double” star, is one of the finest of its kind in the entire night sky. It’s easily found, thanks to its convenient location beside Vega, with sharp-eyed observers being able to detect two stars without optical aid.

However, not everyone has perfect vision (or perfect skies!) and so it appears as a single star to the vast majority, but binoculars will easily split the star in two. Even 8×32’s will show a close pair of white stars of equal brightness, but it’s when you turn a telescope toward it that the magic truly happens.

A magnification of 100x or more will split each star in two (although if the air isn’t steady you’ll need a higher magnification.) You’ll see two pairs of white stars, of almost equal brightness, thereby giving rise to its nickname – the “double double.”

(Incidentally, although the four stars were first seen by Christian Mayer in 1777, it was William Herschel, discoverer of the planet Uranus, who gave the star its nickname two years later.)

These four stars make up a true multiple star system, roughly 160 light-years away, with the northerly pair known as Epsilon1 and the southerly pair known as Epsilon2. The two pairs are separated by 0.17 light-years and take hundreds of thousands of years to orbit one another, with the two stars in each pair taking hundreds or thousands of years to orbit each other.

As if that isn’t complicated enough, there’s a fifth star that orbits one of the stars of Epsilon2. Discovered in 1985, it’s it’s thought to have an orbital period of less than 100 years, but otherwise not much else is known about it.

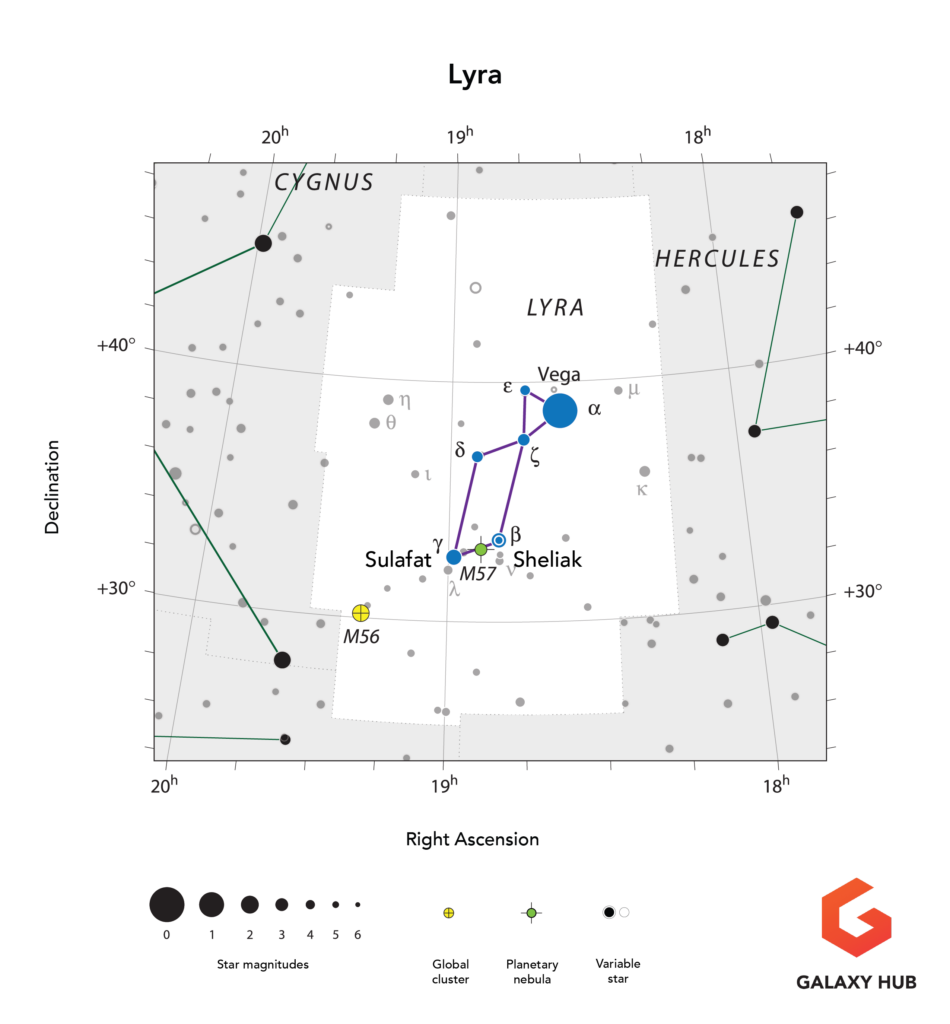

Lyra’s Deep Sky Objects

| Object | Name(s) | Type | Mag | R.A. | Dec. | Distance (LY) | Min. Equipment |

| M57 | The Ring Nebula | Planetary Nebula | 8.8 | 18h 53m 35s | +33° 01’ 45” | 2,567 | Small Telescope |

| NGC 6791 | N/A | Open Cluster | 9.5 | 19h 21m 40s | +37° 48’ 30” | 16,000 | Small Telescope |

| M56 | N/A | Globular Cluster | 8.3 | 19h 16m 36s | +30° 11’ 01” | 32,900 | Small Telescope |

Planetary Nebulae

M57 – The Ring Nebula

Without a doubt, Messier 57 (M57), the Ring Nebula, is one of the showpieces of the sky. Like its neighbor M56, the Ring was discovered in January 1779 by Charles Messier, and the nebula has since become a favorite of amateur astronomers worldwide.

The Ring Nebula is a fine example of a planetary nebula, so-called because they can sometimes resemble the small discs of planets when observed telescopically. However, that’s only the case here if you’re looking with binoculars or a small telescope at low power, as there’s no mistaking its shape otherwise.

To find it, you only need to look between Beta Lyrae (Sheliak) and Gamma Lyrae (Sulafat.) It’s just 0.8 degrees from the former and appears roughly midway between that star and HR 7162, a magnitude 8 star just to the west of Sulafat.

It’s possible to detect M57 with binoculars, but like M56, you won’t see anything more than a tiny, slightly misty star-like point, thereby making this best left to telescopic observers. Small scopes at low power will show a light gray oval patch, while increasing the magnification to around 70x will start to reveal its shape.

At that magnification, using averted vision, you’ll notice that the central area is darker than the rest of the nebula. The hole at the center becomes more apparent at around 100x, giving the nebula the appearance of a tiny, slightly oval smoke ring in space. It’s this shape, plus the ease with which it can be found, that makes the Ring Nebula a favorite with observers everywhere.

Larger scopes can show hints of a blue-green color and variations in brightness, while the nebula itself seems roughly ill-defined at the ends of its longer axis.

Planetary nebulae are shells of gas and dust expelled by stars as they near the end of their lives. Over time, those shells expand and become visible to observers, like us, many light-years away. This presents us with a challenge – spotting the central star that gave rise to the nebula in the first place.

In the case of the Ring Nebula, the central star was discovered towards the end of the 18th century by the German astronomer Count Friedrich von Hahn. If you want to see it for yourself, you’ll most likely need a scope with an aperture of at least 400mm, a magnification of 300x and excellent seeing conditions.

The Ring Nebula is about 2,600 light-years away and is estimated to be about one light-year in diameter.

Open Star Clusters

NGC 6791

When you think of Lyra, the chances are you don’t think of NGC 6791. This obscure open cluster will often be overlooked in favor of both M56 and M57, but if you own a telescope, it can still be worth tracking down.

You’ll find it close to the eastern border of the constellation, but with no bright stars nearby, you might need a little help in locating it.

One method is to start with Delta Lyrae and then look to the east for a pair of magnitude 4.4 stars, Eta and Theta Lyrae. Both will appear within the same 10×50 binocular field of view (roughly 6.5 degrees) as Delta. NGC 6791 lies just under a degree east of Theta, the southerly orange star of the pair.

It’s detectable in scopes as small as 60mm, but only appears a small, faint circular patch. Larger scopes, of around 200mm aperture or larger, will show a fairly dense but evenly distributed clump of stars. Be sure to use a magnification of 100x or higher.

NGC 6791 is estimated to be about 16,000 light-years away and nearly 50 light-years in diameter.

Globular Star Clusters

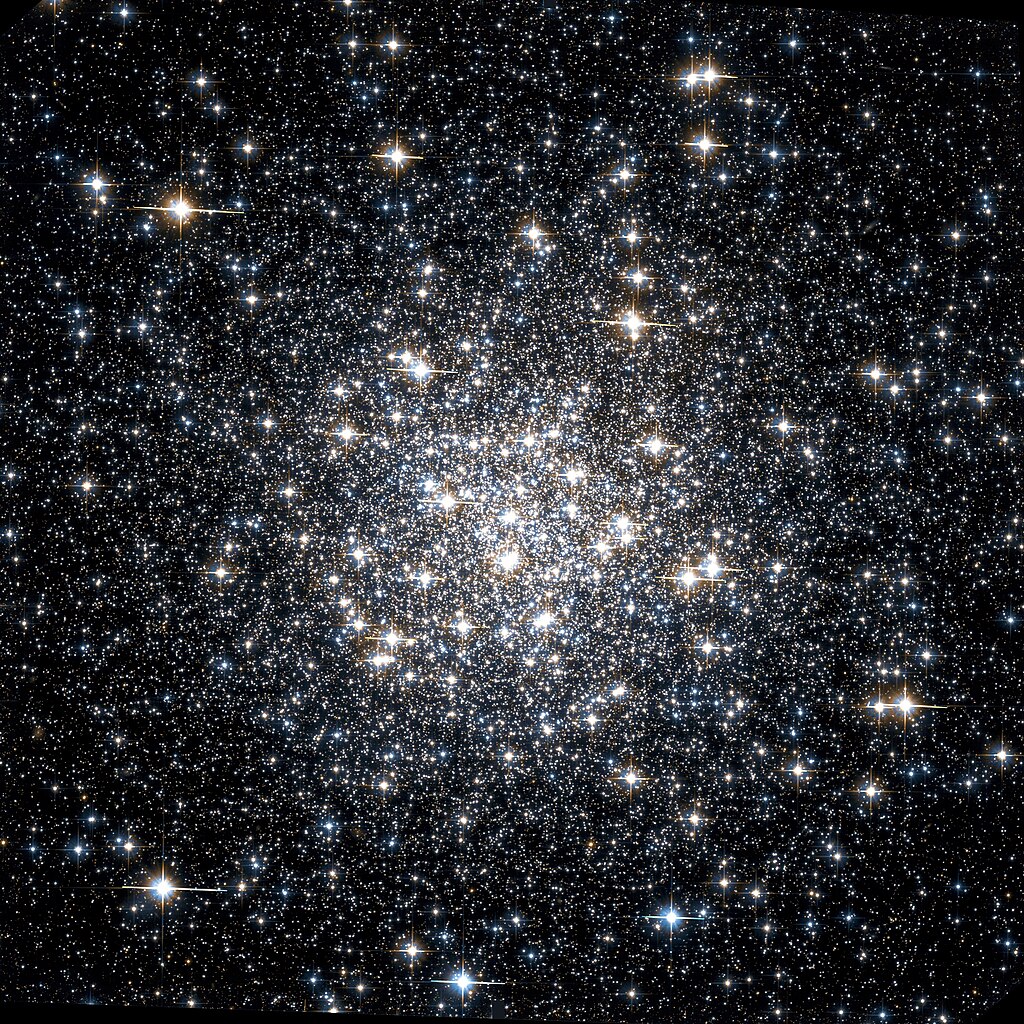

M56

There are two Messier objects in Lyra, with M56 often being overshadowed by M57, the famous Ring Nebula. M56 was discovered by Charles Messier in January 1779, but it lacks the brightness of other globulars, and like NGC 6791, it lies some way from the brightest stars of the constellation itself.

You’ll find it about midway between Sulafat (Gamma Lyrae) and Albireo (Beta Cygni), close to where the borders of Lyra, Cygnus and Vulpecula meet. It appears within the same 10×50 binocular field of view as both Sulafat and Albireo, but is about 45 arc-minutes closer to the latter star. Look for 2 Cygni, a magnitude 5 star, 2.2 degrees to the northwest of Albireo – M56 lies 1.7 degrees to its west.

You can spot M56 with binoculars, but it’ll only appear as a slightly misty star, so if you don’t know what you’re looking for (or where to look for it) you’ll probably miss it. A small telescope at low power (around 30x) will show a faint, circular, light gray misty patch, but if you live under moderately light-polluted skies it may not be found at all.

Mid-sized scopes (around 200mm or larger) will show a bright core, with some resolution in the halo and a few individual stars visible near the cluster’s center. The cluster as a whole lacks both density and the chains of stars that are a frequent sight in similar clusters.

M56 is about 31,000 light-years away and is thought to be about 85 light-years in diameter.