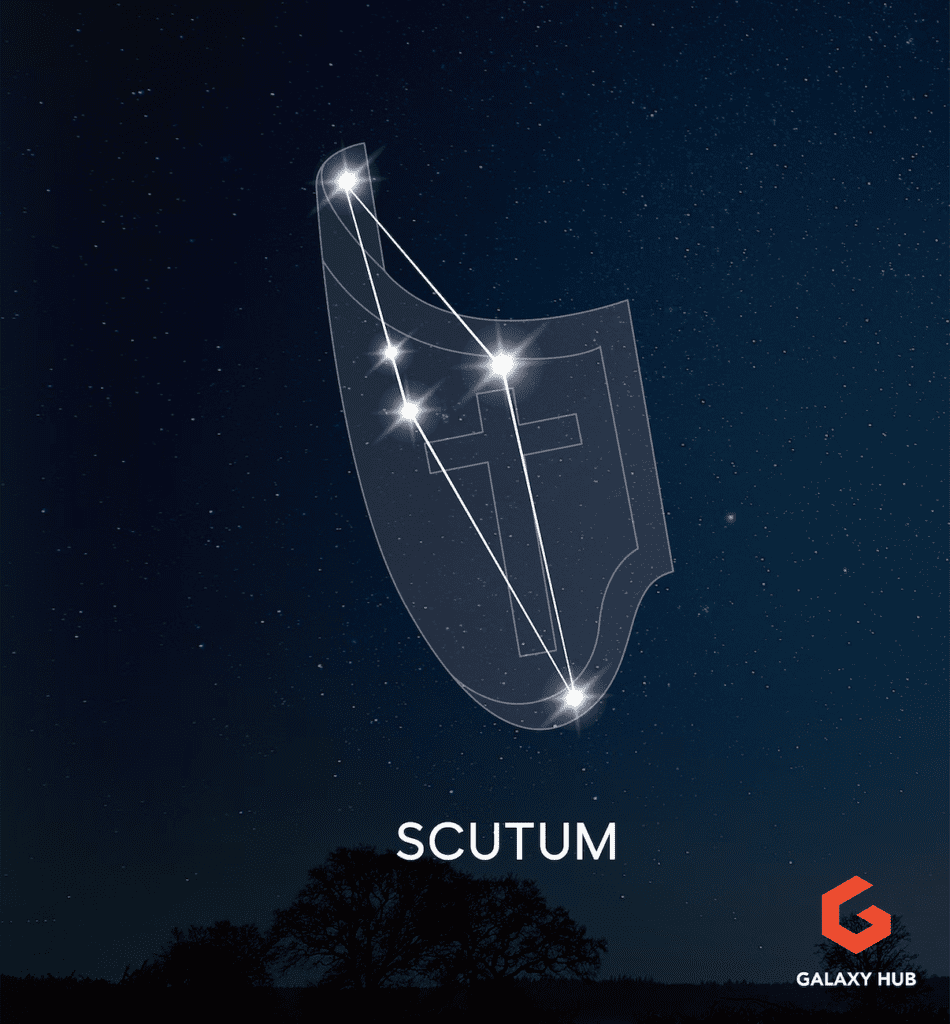

A modern constellation, Scutum was invented in the 17th century by Johannes Hevelius to honor the Polish king, John III Sobieski. It’s a small, faint constellation with just a few objects of interest; in particular, M11 (The Wild Duck Cluster) and M26 are worth seeking out, but otherwise it’s pretty barren. Scutum is best seen from the southern hemisphere, but is visible throughout most of the world from early July to mid-August.

Scutum – Key Data

Name

| Latin | English | Pronunciation | Genitive | Abbreviation |

| Scutum | The Shield | SCOOT-um | Scuti | Sct |

Location

| Hemisphere | Best Seen | R.A. | Declination |

| Southern | Early July to Mid-August | 18h 41m 15s | -09° 58’ 46” |

Features

| Area | Size Rank | # of Messier Objects | # of Stars Brighter than Mag 4 | Brightest Star |

| 109 sq. Deg. | 84th | 2 | 1 | Alpha – Mag 3.8 |

Top Scutum Facts

- Invented by Johannes Hevelius in 1684

- Originally named Scutum Sobiescianum, the Shield of Sobieski, after King John III Sobieski of Poland

- The brightest star, Alpha, is named Ionnina

- Delta Scuti will be the brightest star in the sky in roughly 1.2 million years

- Contains two Messier objects: M11 (the Wild Duck Cluster) and M26

Scutum in Mythology

Scutum is a modern constellation in the southern hemisphere and, consequently, was not known to the Greeks and has no myths associated with it.

Scutum in History

The stars of Scutum are not bright, by any means, and it’s therefore no surprise that ancient astronomers almost competely ignored this area of the sky. The exception would be the Chinese, who knew the stars as Tien Pien, the Heavenly Casque.

The rest of the world apparently ignored these stars until the late 17th century, when the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius invented the constellation in 1684. Originally named Scutum Sobiescianum (the Shield of Sobieski) it was named in honor of the Polish king, John III Sobieski, who had defeated the Turks the previous year.

Hevelius took the faint stars to be found here and used them to form a shield, with the four stars on the border of the shield representing the king’s four sons. Over time, the constellation’s name was shortened to just Scutum, but the king’s name remains in Ionnina, the name of Alpha Scuti, the constellation’s brightest star (see below.)

When & How to See Scutum

Scutum is best seen in July and August, which of course is summer in the northern hemisphere and winter in the southern hemisphere. Being below the celestial equator, it’s best seen from the southern hemisphere but can still be seen throughout much of the north.

The constellation itself is easily located, as it shares a border with Aquila, the Eagle, to its northeast. However, the stars are faint and are best located by first finding Lambda Aquilae, the magnitude 3 star that marks the tail feathers of the eagle. Beta Scuti (mag 4) lies nearly five degrees to the west (and within the same field of view of many binoculars) while Alpha, the brightest star, is nearly eight and a half degrees to the southwest.

Scutum’s Notable Stars

| Bayer/Flamsteed Designation | Name (s) | Mag | R.A. | Dec. | Distance (LY) | Notes |

| Alpha / N/A | Ionnina | 3.8 | 18h 36m 27s | -08° 13’ 34” | 199 | Scutum’s brightest star |

| Delta / N/A | 4.7 | 18h 36m 27s | -09° 01’ 51” | 202 | Variable star | |

| R / N/A | 5.4 | 18h 48m 42s | -05° 40’ 50” | 1,400 | Variable star | |

| UY / N/A | 9.3 | 18h 28m 52s | -12° 27’ 10” | 9,500 | Variable star |

Alpha Scuti (Ionnina)

To say that Ionnina is Scutum’s brightest star is almost misleading, as it’s not particularly bright (magnitude 3.8) and is the only star brighter than magnitude 4 in the entire constellation. It’s barely visible under suburban skies, but you’ll need to allow your eyes to adapt to the dark first.

A K3 III orange giant in the later stages of its life, it was once considered a part of Aquila and even had the Flamsteed number of 1 Aquilae. Its name, Ionnina, is Greek and means “Of John”.

According to Jim Kaler, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy at the University of Illinois, this could refer to the “shield within a shield,” which was known as the Janina design, but Richard Hinckley Allen, in his book Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning ties the name John to the constellation as a whole (see above.)

Ionnina is estimated to have a radius of about 20 times that of the Sun and to be about 33% more massive. It lies at a distance of 199 light-years.

Delta Scuti

Delta is Scutum’s fifth brightest star and the prototype for Delta Scuti variable stars.

It changes in magnitude from 4.60 to 4.79 over a short period of just 4.65 hours, but while its period makes it possible to observe changes over the course of a single night, the small variability (0.19 magnitudes) make it a more challenging target. The changes in magnitude are caused by the star pulsating.

A white giant star, of spectral type F2 III, Delta is estimated to be about 800 million years old and a little more than twice as massive as the Sun. It also has two stellar companions, and while the system is currently just a little further away than Alpha Scuti (202 light-years), that won’t always be the case.

If it continues on its projected path, it will pass within 10 light-years of the Sun and become the brightest star in the sky, with an estimated magnitude of -1.8 (compared to -1.5 for Sirius.) That said, you’ll need to wait around 1.2 million years to see it!

R Scuti

R Scuti can be found just a degree to the northwest of Messier 11, the Wild Duck Cluster. Like Delta, it’s a pulsating variable, but with a much wider range.

At maximum, it shines at magnitude 4.2, placing it well within naked-eye visibility, while at minimum it withers to magnitude 8.6 and requires binoculars or a telescope to spot it. An RV Tauri type variable, it has one of the longest periods of its kind (nearly 147 days) and is known to erratically vary in brightness.

Scutum’s Deep Sky Objects

| Object | Name(s) | Type | Mag | R.A. | Dec. | Distance (LY) | Min. Equipment |

| M11 | The Wild Duck Cluster | Open Star Cluster | 5.8 | 18h 52m 18s | -06° 14’ 24” | 6,100 | Binoculars |

| M26 | Open Star Cluster | 8.0 | 18h 46m 33s | -09° 21’ 36” | 5,400 | Binoculars | |

| NGC 6712 | Globular Star Cluster | 8.1 | 18h 54m 18s | -08° 40’ 44” | 23,000 | Binoculars | |

| IC 1295 | Planetary Nebula | 12.5 | 18h 66m 50s | -08° 48’ 08” | 4,700 | Telescopes |

Star Clusters

M11 – The Wild Duck Cluster (Open Star Cluster)

Scutum isn’t known for its deep sky objects, but Messier 11 (M11), the Wild Duck Cluster, is certainly worth seeking out. It’s easily found, close to the stars that mark the tail feathers of Aquila the Eagle.

It lies about four degrees to the southwest of the magnitude 3.4 star Lambda Aquilae. As such, it’ll fit within the same binocular field of view as the star, but otherwise, look for the stars Iota Aquilae (mag 4.0) and Eta Scuti (mag 4.8), as they will also point the way.

Through binoculars, it appears small, compact, faint and almost globular, with a star-like point on the north-eastern edge. Using averted vision will help to draw it out.

A small telescope at a low magnification of around 35x will show a granular V-shape (hence the cluster’s name – it resembles ducks in flight) with the single bright star at the tip. Otherwise, the stars appear of uniform brightness.

Increasing the magnification will reveal more stars, but at the cost of losing the cluster’s shape. Larger apertures will also show chains of stars separated by dark lanes, not unlike a globular cluster.

M26 (Open Star Cluster)

M26 is smaller than M11 and lies about three and a half degrees to that cluster’s south, and two and three quarter degrees to the east of Ionnina (Alpha Scuti), the constellation’s brightest star.

That places it within the same binocular field of view of both, but at magnitude 8.0, it may prove tricky to spot from a suburban sky. Since this is also smaller than M11, you’ll need a higher magnification to get the most out of it.

A small scope at a magnification of around 100x will show a few dozen stars, while larger apertures will reveal about a dozen more. It’s a compact cluster comprised of stars of varying brightness, with a few clumps and chains of stars being apparent.

NGC 6712 (Globular Star Cluster)

Like M26, NGC 6712 lies to the south of M11, but whereas M26 can be found three and a half degrees to the south, NGC 6712 is a shorter two and a half degrees south and slightly to the east.

As with many globular clusters, it’s detectable in binoculars, but best observed with a larger telescope of 250mm aperture or larger. Don’t expect anything too spectacular; it’s slightly misshapen, with an unresolved core that’s a little brighter than the surrounding halo.

Nebulae

IC 1295 (Planetary Nebula)

If you have a larger scope and are looking for a challenge, try your hand at IC 1295. It’s just under half a degree to the southeast of NGC 6712 and should therefore fit within the same field of view at low power.

That said, you’ll need a scope with an aperture of at least 250mm to see it.

At first glance, it appears as a very pale, circular glow, not unlike a distant galaxy. Look out for a pair of faint stars on the nebula’s southwestern edge. The central star will remain beyond the view of most amateur equipment, requiring an aperture closer to 500mm to spot it.